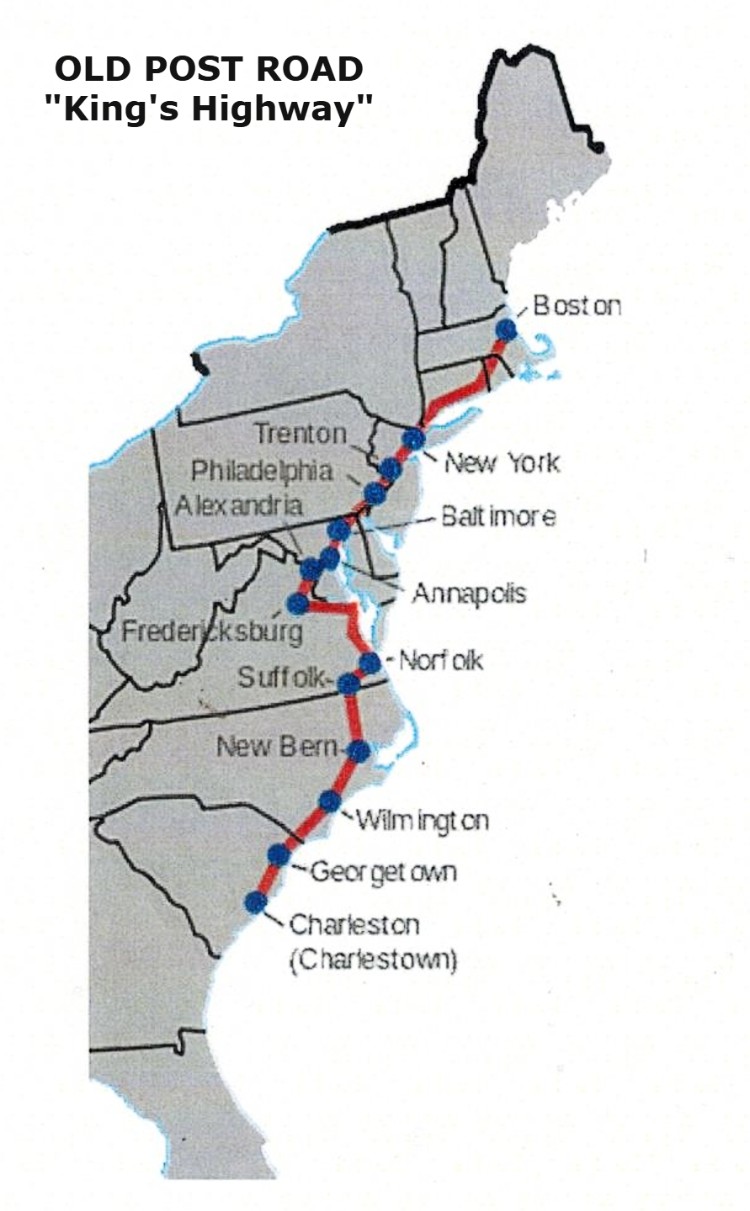

Continuing our America250 posts, this 2nd post highlights Old Post Road, also known as ‘King’s Highway.’ We wanted to share some comments and research as to what it was like to travel Old Post Road in the 1700s. It was definitely not for the faint of heart.

We want to give a special thank you to Robert (Bob) Magee for the notes and research given to us. The notes and research are both his and the late Elsworth Shank, who gave many lectures through the Susquehanna Museum at the Lockhouse.

The following excerpt from from MSA.MARYLAND

The Chesapeake Bay and its multiple tributaries provided the principal means of transportation for 17th century Marylanders. Gradually, as settlements expand beyond navigable bodies of water, roads become more important for the movement of people and goods. The first road law in Maryland, passed in 1666, provided for the construction and maintenance of highways and of passages over streams and swamps suitable for horse and foot. Only later does transportation by wagon become an important factor in the construction and maintenance of roads. The commissioners in each county, composed of the county justices, were required to determine what roads were needed, appoint road overseers, and levy taxes. In lieu of taxes, citizens could furnish labor for road work.

The overall effect of this general road law that remained in effect for 30 years was meager. Many roads continued to resemble mere paths from one place to another. The overseers provided minimum services by removing underbrush, cutting trees, and draining marshy areas. In 1696 and 1704, the legislature enacted more comprehensive laws in order to improve conditions. Main roads were supposed to be at least twenty feet wide and kept clear and well grubbed. The county commissioners were required annually to list all public roads and appoint overseers. Instead of paying taxes, residents were required to work on the roads, or provide laborers, for a specified number of days per year. Fines could be imposed for failure to comply.

Some of the early roads were established by widening trails used by the Indians. Many routes began or ended at a body of water,

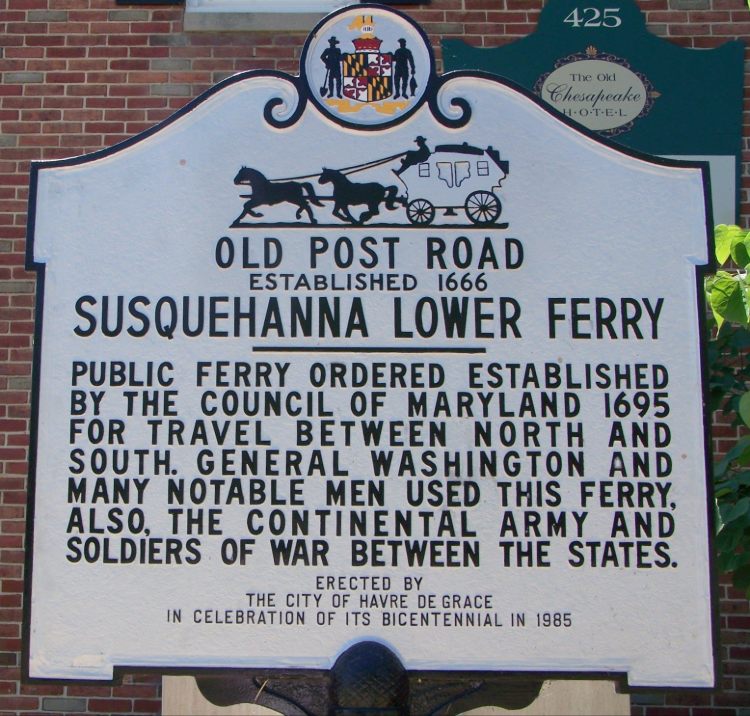

Maryland’s first road law was passed in 1666.

It ordered county commissioners to make highways and paths passable for persons on horse and foot by 1668. In each county, overseers were to be appointed, and either tobacco or labor was to be assessed against county taxables. Compelling county residents to work a certain number of days per year on county roads was rooted in English feudal custom, and became a long-lasting tradition in Maryland. An act of 1704 also required roads to be made passable but was more specific: the roads were to be cleared and grubbed to a width of twenty feet; substantial bridges built where needed; trees alongside notched to indicate if the road led to a ferry, courthouse, church, or to Annapolis or Williamstadt; the public roads recorded annually in the county records; and fines set for any person failing to do his road duty (Chapter 21, September Session, Acts of 1704). Despite the volume of road legislation in the eighteenth century, travel on Maryland roads remained a harrowing experience according to contemporary accounts.

From MSA.MARYLAND

WASHINGTON, LAFAYETTE, and ROCHAMBEAU

Harford County 1660 – Present

“Old Post Road” aka King’s Highway

The following is an excerpt from a letter to Elizabeth Willing Powell, wife of the Philadelphia Mayor. March 26, 1797

I am about to fulfil the promise I made, of giving you an Account of the Stages on the Road.

(NOTE: this excerpt pertains to the Havre de Grace area)

…Between Elkton and the Ferry at Havre de Grace, a distance of seventeen miles of very bad road, there is no house in which decent lodgings could be had; but at Charlestown, rather more than halfway, a brick tavern could furnish breakfast & feed for horses; higher expectations would, probably, be disappointed.

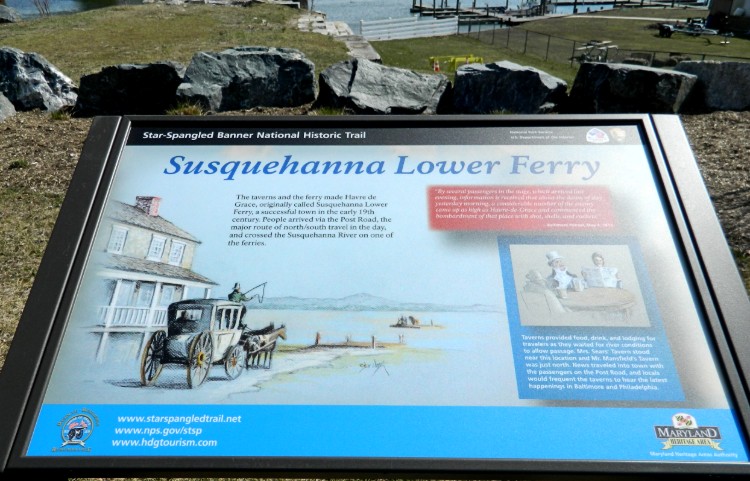

At the Ferry, on both sides, are good Taverns: Mrs. Rodgers’ on the East, & Mr. Barney’s on the West.

From thence to Hartford (commonly called Bush Town) twelve miles from the Ferry, a good house used to be kept-but as it was to be sold the Wednesday after we passed it, I can give no acct of the present occupant.

EXCERPT FROM Harford County Maryland in the Revolutionary War, America’s 250th Anniversary, by Jack L. Shagena, Jr. and Henry C. Peden, Jr. (book available at BAHOUKAS ANTIQUE MALL, Havre de Grace)

The troops under General Lafayette were all from Northern States, and though they willingly engaged in the expedition down the [Chesapeake] bay, they became dissatisfied when ordered to engage in a summer campaign in the South. They were poorly clad and without shoes, and showed much discontent that when they left Bald Friar Ferry, not one-half of them would reach Baltimore.

After Lafayette passed through Harford County and reached Baltimore on April 18th (1781), he wrote Gen. Washington stating:

When I left Susquehanna ferry, it was the general opinion that we could not have six hundred men by the time we should arrive at our destination/I made an order for the troops, wherein I endeavoured to throw a king of infamy upon desertion, and to improve every particular affection of theirs. Since then, desertion has been lessened. Two deserters have been taken up; one of whom has been hanged to-day, the other (being an excellent soldier) will be forgiven, but dismissed from the Corps, as well as another soldier who behaved amiss.

Not far behind Lafayette in early September 1781, Gen. Washington and his troops convened at the Head of ElK enroute to Yorktown. Under his command were 1200 French troops that were accompanied by Claude Blanchard who kept a journal, which was later published. Blanchard noted the, “Head of Elk is in very dry soil, and one is drowned with dust there. Fever is very prevalent there, doubtless caused by the swamps in the vicinity.”

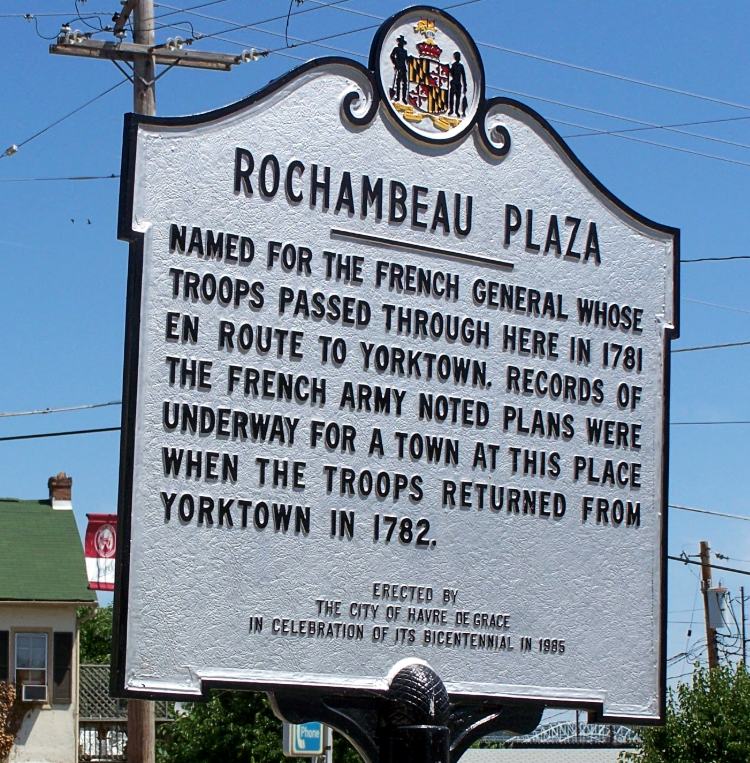

Count Rochambeau and his French troops arrived at the Lower Ferry on the Susquehanna River opposite present-day Havre de Grace in early September 1781. Men and supplies were transported across using rented flat-bottom boats …

At the intersection of Market Street [should be St. John] with Washington Street in Havre de Grace is a Maryland historic marker identifying “Rochambeau Plaza.” It recognizes his troops passing through in 1781 enroute to Yorktown.

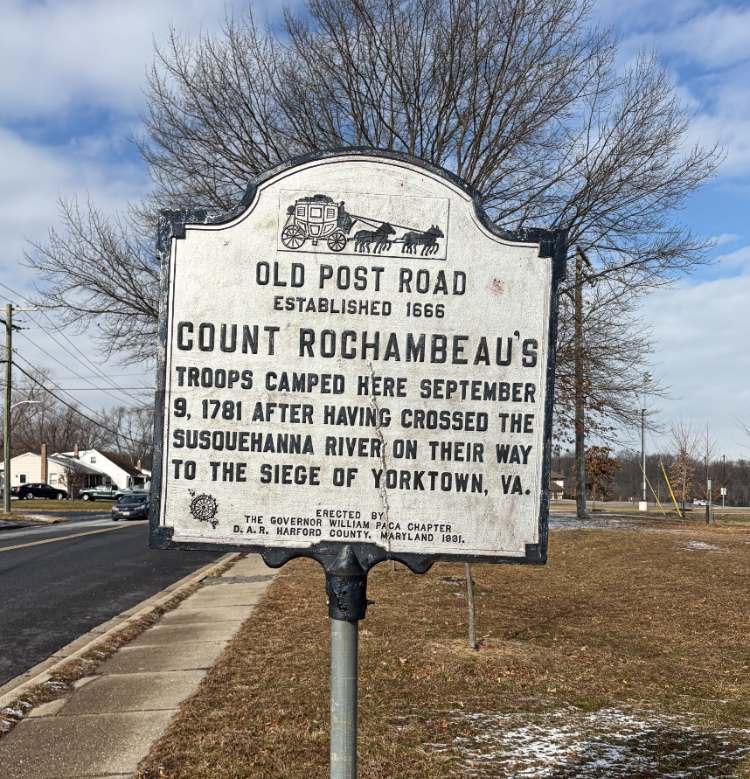

On September 9, 1781 a short distance south of Havre de Grace, Count Rochambeau and his troops camped at a site along the Old Post Road. This location, at the present-day intersection of Revolution Street and Lewis Lane, is identified by the Maryland historic marker shown. (Going west on Revolution, turn right on Lewis Lane, and the marker sits among a couple trees a few hundred feet from the intersection.)

Photo by George Wagner, 2026

NOTE: Markers from Historical Markers Database

A few highlights of Old Post Road from Elsworth Shank’s lecture notes:

For over 150 years this road will be the transportation route for our leaders, the everyday citizens, stage coaches, and materials. Let’s review what it was like to travel on this important highway and some of those who wrote of their experiences. We will be going briefly through the travel in Harford County although until 1785 the area was chiefly known as Baltimore County, which extended to the Susquehanna River.

This photo by Ken Lay (thanks to Steve Lay) would now be Route 155 and the bridge is the B&O Railroad Bridge.

But it’s a good representation of the roads in the 170ss.

- Early on there were no bridges over streams. When you came to a stream, you just waded in.

- Coming to a river required the use of a ferry, and you were at the whim of the ferryman. Service was erratic at best, and the traveler was at the mercy of ice, rain, wind, and drunken ferrymen.

- When the stages became bogged down, the passengers had to get out and push it out of the mud or over the obstacle.

- Taverns grew up along the road and existed every ten or twelve miles.

- In 1735, an order to standardize service and quality was issued. “Ordinaries” were established. Licensees were established, licenses were issued and standards were set.

Old Ordinary c. 1820- Havre de Grace – photo by Ken Lay (1930) – located at Congress Ave and St. John Street

- Fees, cleanliness, and the number of beds in a guest room were determined by law. Usually there were no rooms with only one bed, you slept with other travelers.

- People traveled on foot, horse or stagecoach. The coaches traveled about 3-4 miles per hour on ‘good’ days!

- The roads were horrible throughout the length of the road but were especially worse in Maryland.

- There were tree stumps in the roads, and the roads went through marshes, forests, and streams.

- During rain or snow, the roads were almost impassable. [It helped Havre de Grace because travelers had to stay here for several days while the weather was bad.]

Same area as the photo above (Ken Lay).

Another photo by Ken Lay – same area in winter.

From Heidi Gladfelter’s book, Havre de Grace in the War of 1812, she wrote that ‘whether on foot or in coaches, the roads were difficult to travel. A traveler could take a stagecoach from Boston to Savanna, Georgia in 24-days and taverns became the respites where weary travelers could get a meal and a good night’s sleep.

- Because newspapers were rare, taverns became a center for the exchange of information.

- Stevenson Tavern (Perryville) became the famous Rodgers Tavern.

As late as 1774, from an account by a Dr. Hamilton:

The inns were excellent. {many others will disagree] Breakfast was a half-dollar and dinner was a dollar. This included brandy or rum. Sleeping conditions were generally poor.

George Washington wrote that “travel by stage was not luxurious.” He wrote that he “had to abandon many a stage after traveling through Maryland due to the poor roads.

Editorial in Maryland Journal 1785: “It is a truth that we are all agreed, that our roads, without an exception, are in the most ruinous condition; that it is extremely difficult, and even dangerous for either carriages or horses to travel on our roads…and that our agriculture and commerce are hurt by these conditions.”

One traveler complained that “Tree stumps lined the upland sections of the road beds, while the lowland stretched, laid out in through streams and marshes, and were routinely rendered impassable by rain and snow.

- Walking was no better since they had to wade through streams, the water and mud went into their shoes.

Another account from a Dr. Hamilton, in 1774, “I came to Joppa, a village pleasantly situated and lying close upon the river. There I called at one Brown, who keeps a good tavern in a large brick house. The landlord was ill with intermittent fever and he asked my advice, which I gave him.”

Another interesting account from Dr. Hamilton:

“Traveling north stopped at a tavern at the Susquehanna River kept by a little old man whom I found eating vittles with his wife and family upon a homely dish of fish without any kind of sauce…in a dirty, deep, wooden dish which they evacuated with their hands, cramming down skins, scales and all. They used neither knife, fork, spoon, plate nor napkin because I suppose they had non to use.

The couple desired me to eat, but I told them I had no stomach. “ Once he crossed the river into Cecil County, he ate at the tavern there.

December 13, 1778 account from artist, Charles Wilson Peale:

“Staying in Havre de Grace, sett forward and got to Bush Town (Harford Town) to dinner – distant 14 miles. It having rained all last night and great part this morning, the runs were raised so high as to make it dangerous to ford them. I was constrained to stay here this night and in the evening a good deal of company arrived. Amongst them some officers of Colonel Bayler’s Light Infantry Horse, all Virginia, whom from a general observation are much addicted to swearing, much more than any of the northern states…one reason (for Southerners swearing) according to Peale, is the great number of slaves which they have there and, being accustomed to tyrannize and dominate over.’

June 27, 1788, Peale wrote:

Colonel Ramsey and Betsy being on party in Havre de Grace and did not go down to the point…we spent the evening together at Mr. Baxter’s,,. where we slept. On June 28, I rose at 3 o’clock at which hour none of the stage men were stirring. Soon after they rose and began to prepare to set out. The wagon was so crowded, he had to leave one of his cases behind.”

Many dignitaries traveled the Post Road. And of course,George Washington, was a frequent traveler. He stayed often at Rodgers Tavern in Perryville and at the Rodgers Tavern/House and subsequently Barney’s (John Barney – brother of Commodore Barney’. Washington kept a diary and in it he always had the weather and conditions. Because of him, I (Elsworth Shank) can almost recite his travel through this area to Philadelphia.

For more details about Rodger’s Tavern in Perryville, visit their Rodger’s Tavern Museum website.

March 1797 (George Washington) example of trip from Philadelphia:

March 10 dined and lodged at Elkton (Head of the Elk). At Elkton…Hollingsworth’s is a quiet orderly tavern, with good beds, and well in other respects. Eather – tolerable pleasant all day.

March 11 – snowing from daylight until 10 o’clock. In the afternoon a little rain. Breakfasted at Susquehanna – dined and lodged at Harford.

“At the ferry, on both sides are good taverns: Mrs. Rodgers on the east and Mr. Barney’s on the west. From then to “Harford” (commonly called Bush Town) twelve miles from the ferry, a good house used to be kept but…it was to be sold the Wednesday after we passed it” (From Washington’s cash memorandum, it could be seen that he stopped at both Rodgers and Barney’s on that day.”

March 12 – Temperature lowering, but tolerable pleasant. Breakfasted at Webster’s. Dined and lodged in Baltimore. (Webster’s was 13 miles northeast of Baltimore.)

Finally, the most interesting account and an example that the Post Road was still the main road of travel through the north and south.

WAR GOING ON – 1778 – Mrs. Washington is going north to meet with General Washington:

LETTER TO A JOHN MITCHELL (Colonel and Deputy Quartermaster General, then at Philadelphia)

Fredericksburg, November 11, 1778

Dear Sir: I have been favoured with your Letter of the 3d. and have received the three Table Cloths which accompanied it; as also the Bear skin, which I accept, and thank you for. The Trunks will do, tho if they had even a size smaller I should have liked them better. The four Table Cloths which preceeded the three above mentioned, are not yet got to hand. I would have you trouble yourself to procure and Bowl; the one I have, can, I believe, be mended.

Colo. Fitzgerald seems to doubt whether Mrs. Washington can get to Philadelphia without the Springs which Mr. Custis (unluckily) prevented his getting; I have therefore, as the Season is growing cold, and the Roads getting bad, to request the favor of you to send them on by a Special Messenger, along the following Rout: Wilmington, Christeen, head of Elk, lower Ferry on Susquehanna, Baltimore, and Bladensburg; by doing which, if Mrs. Washington should have set out, as I have desired her to do if it be praticable and along the Road they will meet. The Springs may then be fix’d at P.

Upon her arrival in Philadelphia I must beg the favour of you to give me notice of it by the lay Expresses, that I may send for her, if my own Quarters for the Winter should happen to be fixed up; But as this is not the case yet, and I do not know when it will be, I cannot, under the uncertainty of her stay in the City, think of accepting yours and Mrs. Mitchells kind and polite Invitation to her to lodge with you; the trouble of such a visitor (for more than a day or so) being too much for a private family but I shall be equally thankful to you for providing good lodgings for her as I do not know how long it may be necessary for her to remain in them. Her Horses you will be so good as to send to the Public Stables (most convenient).

I wish the report of the reduction of the Island of St. Vincent may be true, and think the Troops at New York might be as usefully employed in defence of their possessions in the West Indies, as where they are; but, Ministry I suppose judge otherwise. My best respects to Mrs. Mitchell, I am, etc…

By the end of the 18th century, there were many inns, taverns, and houses for the rich, mills and other businesses, that stretched along the road. These inns and taverns were of critical importance! They became the social centers where games could be played, politics discussed, lodges and patriotic societies could meet and were open to all peoples.

From Chronicles of America website:

Birket tells of passing over the Susquehanna in January on the ice, and describes how the horses were led across and the party followed on foot, with the exception of two women who sat on ladders “and were drawn over by two men, who slipt off their shoes and run so fast that we could not keep way with them.”

I think this quote from the same website article is the perfect end to this post:

“To the early colonists must be given the credit of having laid a broad and stable foundation for the future United States of America, and their subsequent history has been the indisputable record of a growing national solidarity. Even the Civil War, which at first sight may seem conclusive contradiction, is to be regarded as in its essence the inevitable solution of hitherto discordant elements in the democracy which had their beginnings far back in the complex spiritual and social inheritance of the early colonial generations.

From the vantage point of the twentieth century, with its manifold legacy from the past and its ample promise for the future, it has been interesting to glance backward for a moment upon colonial times, to see once again the life of the people in all its energy, simplicity, and vivid coloring, with its crude and boisterous pleasures and its stern and uncompromising beliefs. Those forefathers of ours faced their gigantic tasks bravely and accomplished them sturdily, because they had within themselves the stuff of which a great nation is made. Differences among the colonists there indubitably were, but these, after all, were merely superficial distinctions of ancestral birth and training, beyond which shone the same common vision and the same broad and permanent ideals of freedom, of life, opportunity, and worship. To the realization of these ideals the colonial folk dedicated themselves and so endured.”

AN INTERESTING SIDE NOTE

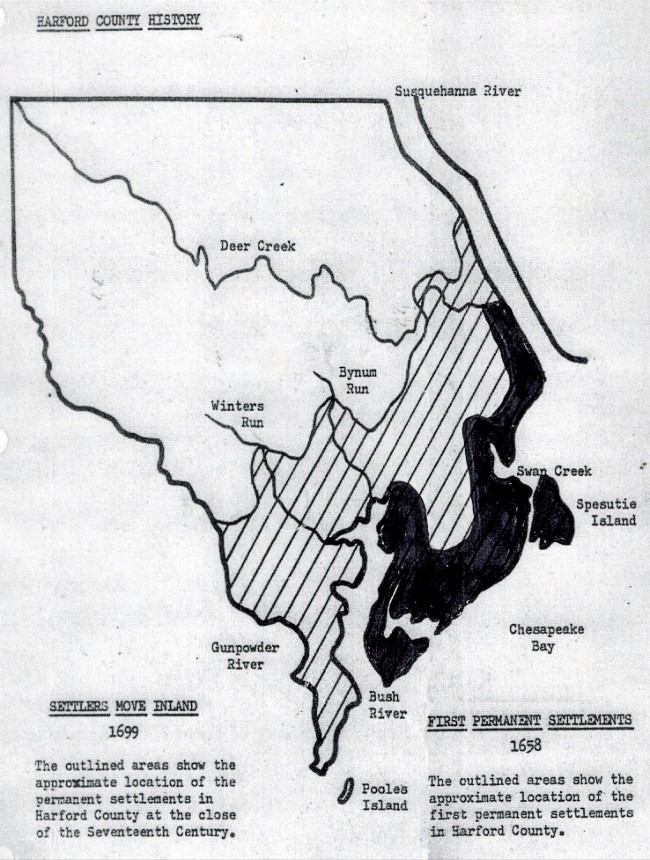

This is a Harford County Map showing the First Permanent Settlements in 1658 (dark black). The striped areas are the permanent settlements at the close of the 17th Century (1699)

In the meantime, our casual historian at BAHOUKAS ANTIQUE MALL, George Wagner, will be sharing tidbits of history and stories over the coming months. He hopes you enjoy reading about them as much as he enjoys the research!