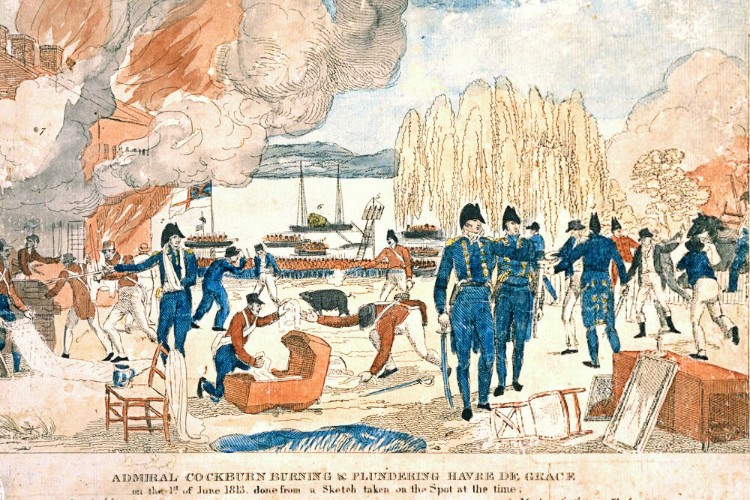

In Episode #3, we shared a bit about the War of 1812. On May 3, 1813, the British ransacked and burned the city. John O’Neill made a valiant effort to stop the British. Below are a few quotes about this event that destroyed half to two-thirds of our city, leaving many citizens destitute with no homes to return to, no belongings, and most likely no way to earn a living. We honor their perseverance!

<an important note – the effect of the heroic effort of O’Neill>

A contemporary newspaper, The Weekly Register, published by H. Niles, of Baltimore, in the issue of May 8, 1813, published the following remarks concerning the destruction of Havre de Grace:

“The ruins of Havre de Grace shall stand as a monument of British cruelty, in which, as in a glass, we may see the true spirit of the government. The villainous deed has aroused the honest indignation of every man–no one pretends to justify or excuse it. It has knit the people into a common bond for vengeance on the incendiaries. It has destroyed party; and by a communithy of interests, effected what patriotism demanded in vain. God forbid that we should be at the mercy of Cockburn and his Winnegabagoes, exalted to the pinnacle of incendiary merit by his attack upon Havre de Grace; a deed that shall be recorded to the lasting infamy of British arms–wanton, cruel and base. The savage burning of Havre de Grace has led the people of Baltimore to calculate what they might expect from the tender mercies of the enemy–and they indignantly assemble to punish the invader.”

from History of Havre de Grace, “The Town We Live In,” by Elias W. Kidwiler, 1947, published by the Havre de Grace Record.

At Havre de Grace a small breastwork had been thrown up at Concord Point, and three pieces, one nine-pounder and two six-pounders, known as the Potato Battery, were mounted. Even in 1812 this battery could not have been called more than a defensive gesture. The name implies ridicule on the part of the townspeople, but there was one man in the settlement who was either deadly serious about this obviously inadequate defense or who was determined to make bese use of the improvisation which it was. The single man on duty at the battery, when he saw the British fleet approaching, gave the alarm. Of all the officers of the state militia assigned to these guns, only a second lieutenant, John O’Neill, was in Havre de Grace when the attack came. His entire command consisted of no more than fifty militiamen. The militia of that time may be compared with the home guard of the scond world war. The members were either over age or men who had been excused from military service because of physical disability or family responsibility. They were lacking in discipline, were not uniformed and were totally untrained.

Lieutenant O’Neill, replying to the alarm sent out by the sentry at the battery, went immediately to his post and was joined by three or four men of his command. They immediately opened fire on the British ships and were answered by a hail of grape and rockets, which was the terrible noise which awakeneed the slumbering residents of the settlement. Perhaps discouraged by the fact that so many of their fellow militiamen showed their lack of interest and influenced in some measure, of course, by the rain of grape and rockets let loose by the British, O’Neill’s men all left the fort unceremoniously and abruptly for a safer place in or near the village, but in any event further away from the scene of action, leaving the lieutenant as the lone defender of the village. He fired one shot at the enemy unassisted, but the gun recoiled, running over his leg and disabling him. Failing in an attempt to rally, the fellows who had deserted the battery and some others of his company he spotted at a distance, he went into town and got a musket with which he returned to a common near the battery and continued firing on the British landing party until his ammunition was exhausted. However, his infividual effort was unable to prevent the landing of a Britich force of 400 men, a number equalling the total poupulation of Havre de Grace at that time. When the British came upon Lieutenant O’Neill with a musket in either hand they placed him under arrent and took him aboard one of the ships.from History of Havre de Grace, “The Town We Live In,” by Elias W. Kidwiler, 1947, published by the Havre de Grace Record.

… “an adequate memorial of his bravery was dedicated November 14, 1914, on the spot near where the 1813 battery once stood. A cannon that was in service during the war of 1812 was presented to Havre de Grace by the (Star Spangled Banner Centennial) Commission; and a granite foundation for the gun was presented by John O’Neill’s descendants and the citizens of the town. The gun bears the following inscription:

This cannon, of the war of 1812, marks the site of the three gun battery on Concord Point, where John O’Neill resisted for a time single handed the Britsih attack on Havre de Grace, May 3, 1813, until he was disabled and made prisoner. He was taken aboard the British firgate Maidstone whence he was rescued by duaghter, Matilda, to whom Amdiral Cockburn presented his gold mounted snuff box in token of her heroism. In recognition of this bravery the citizens of Philadelphia presented John O’Neill with a handsome sword.Erected by the citizens of Havre de Grace in the year of the National Star Spangled Banner Centennial, 1914.”

from Historic Havre de Grace, published by the Havre de Grace Public Library, October 20, 1939.

John O’Neill

217-219 South Washington Street, mid-19th century

Around 1804, John Henry O’Neill (1768-1838) established a nail factory on this lot where the employees made hand-wrought nails and spikes. O’Neill was, of course, the city’s Defender during the War of 1812. Bennet Barnes (sometimes Bennett) was the chief nailmaker and they employed about 19 people. After the 1813 attack by the British at Concord Point, and O’Neill’s wounding, it is said that he retreated to the nail factory with his musket and joined Bennet Barnes in firing on barges.

from Historic Havre de Grace website

218-220 South Washington Street, John O’Neill House, c. 1814; 1865

The home has considerable historic significance to Havre de Grace, since the property was in the O’Neill family for about 158 years. John O’Neill owned the nail manufactory (since demolished) in town, which was located directly across the street from this home. When John O’Neill died, he bequeathed two lots on South Washington Street to his son, William O’Neill, this Lot 241 being one of them, and the other being his nail factory across the street. Upon William’s death, he conveyed this home to his own son, John William O’Neill (1845-1931). The latter, at his death, bequeathed this property in 1928 to The Convention of the Protestant Episcopal Church of the Diocese of Maryland, the Vestry of St. John‘s Parish. The O’Neill family all were members of St. John’s Church.

from Historic Havre de Grace website

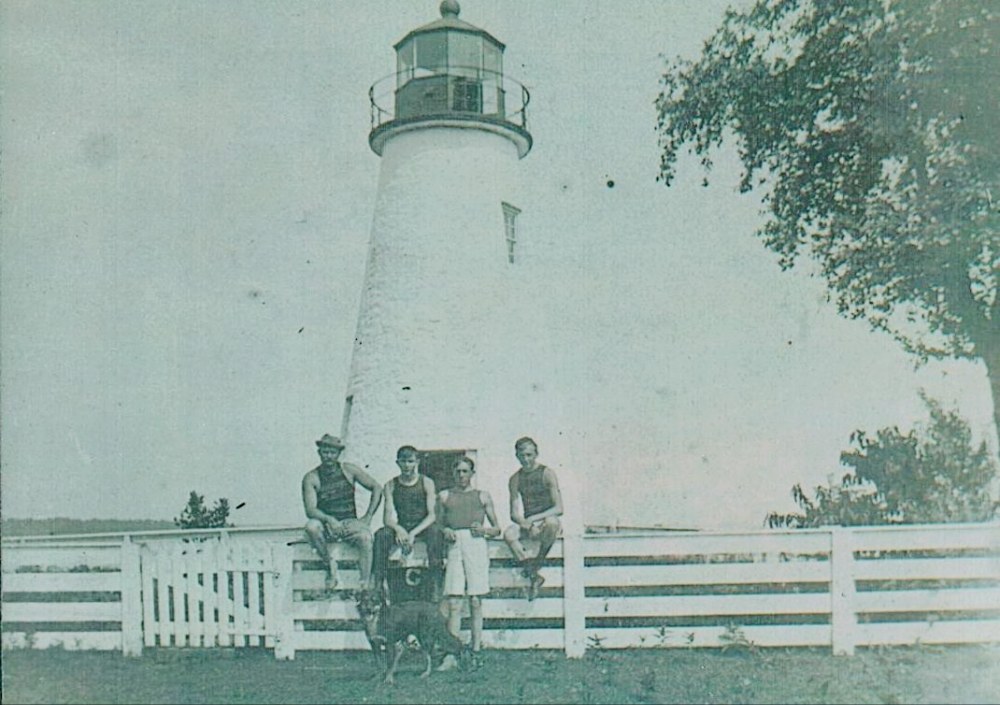

CONCORD POINT LIGHTHOUSE

CLICK HERE to read about the archaeology dig done at the Keeper’s House. Pages 16-19

Lighthouse Keepers

from Concord point lighthouse website

Lighthouse keepers during the early 1800’s were appointed by the President of the United States. Fifth Auditor Stephen Pleasonton would submit the names of all applicants along with his recommendation to the president. In a letter dated October 25, 1827 to President John Quincy Adams,

Pleasonton lists the nine applicants for the lighthouse at Concord Point, including Donahoo, the builder. The letter closes with Pleasonton’s endorsement of John O’Neill, a member of the militia and a hero of the War of 1812.

Keepers 1827

President Adams appoints John O’Neill as keeper on November 3, 1827 for a salary of $350/yr. Lt. O’Neill served as keeper until his death in 1838. Four generations of the O’Neills would serve as keepers at Havre de Grace, a unique situation among keepers of the Chesapeake lighthouses.

Keepers 1839-1919

After the death of John O’Neill, several men served as keepers until John O’Neill, Jr. was appointed in 1861. Thomas Courtney and John Blaney appear to have alternated as keepers until Thomas Sutor was appointed in 1853.

John O’Neill, Jr. was appointed April 12, 1861 and served until his death in 1863. His widow, Esther O’Neill, was official keeper from 1863 until her retirement in 1881. She was assisted by Gabriel Evans, her son-in-law, for some of this time. Her son, Capt. Henry E. O’Neill was made acting keeper in 1881 and promoted to official keeper in 1885. He was the last official keeper and served until his death in 1919. His son, Henry F. O’Neill (Harry) served as custodian/laborer until the keeper’s property was sold in 1920.

Esther O’Neill, widow of John O’Neill, was official keeper from 1863 until her retirement in 1881.

Would you enjoy more info on women light keepers? CLICK HERE

Esther O’Neill – Photo Courtesy Carol Allen, Friends of the Concord Point Lighthouse

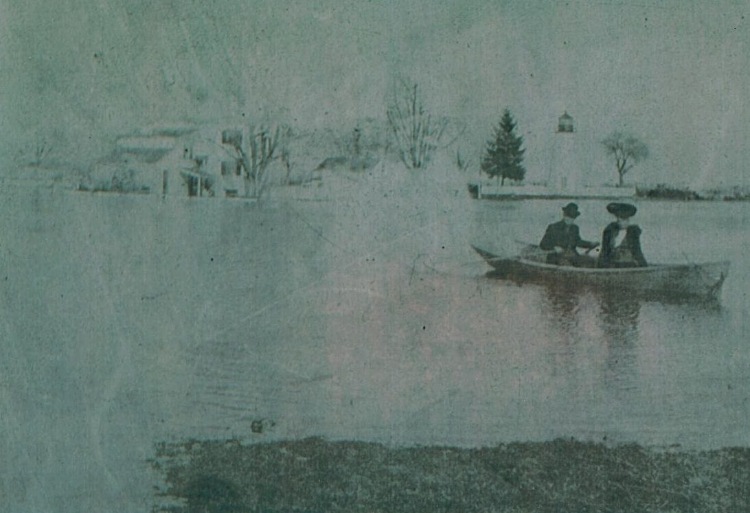

In 1826, the State of Maryland authorized the city to transfer the end of Lafayette Street to the federal government. In May of 1827 the federal government signed deeds for both the 22 foot square plot on the riverbank and a 1 acre parcel landside. This unusual arrangement meant the keeper’s quarters would be 200 feet from the lighthouse, a sizable distance in poor weather.

Originally illuminated with 9 whale oil lamps with 16 inch reflectors, the Lighthouse was upgraded with a Steamer’s lens in 1855 and a 6th order Fresnel lens in 1869.

Picture a dark, rainy night when the keeper would have to row a boat to the lighthouse, and climb the 27 slippery, granite steps and the 8-rung ship ladder, through the trap door to light those 9 whale oil lamps!

The Keeper’s House

from Concord point lighthouse website

The original contract for the keeper’s house gives the clearest picture of the keeper’s property built in 1827. No known photographs exist until

after renovations in 1884.

The original dwelling house, also built of local granite, was 34 by 20 feet

with an attached kitchen, 14 by 12 feet. The first floor was divided into 2 rooms,

with a chimney and 3 windows in each and an entry in between.

The half-story above had 2 sleeping chambers, each with a window.

The basement went the full length of the house with the stone walls 20 inches thick. The kitchen included a chimney with a fire place, a sizable oven, a sink with a spout through the wall, 2 windows, an outside door and a door to communicate with the rest of the house. The contract also specified a stone privy and a well.

The Havre de Grace Light Station, as it was officially known, went into service in November 1827 for a total cost of $3500. It was always known locally as

Concord Point Lighthouse.

In looking back, we pay tribute to the hardy citizens

who continued to put their shoulders to the wheel,

creating the city we enjoy today. Their perseverance,

even when half to two-thirds of the town was burned in 1813,

leaving many families homeless and destitute, was steadfast.

It’s also interesting to note that our fine city, with its amazing historic buildings, is a result of residents caring about our history over the centuries.

George, our casual historian, encourages you to visit the main blog page and scroll through the posts for more stories. You are also encouraged to stop in at Bahoukas Antique Mall and browse more than a dozen cases and a huge wall of Havre de Grace History memorabilia! Be sure to say ‘hi’ to George!

Stay tuned for our next blog post – #5 and #6 Havre de Grace – a growing city.